The steam packet Pulaski left Charleston Harbor 180 years ago and quickly met an end off North Carolina's coast where its boiler blew, cutting the ship in two and sending more than half its passengers and crew to their death.

It's a largely forgotten story, though at the time it was the young American nation's most lethal passenger ship sinking in its history.

Some have likened it to the Titanic of its day, and its death toll was surpassed only by the loss of the USS Wasp en route to the Caribbean in 1814.

But the Pulaski's story is resurfacing, literally bit by bit, as a maritime group recently confirmed its wreckage about 40 miles off North Carolina's coast.

James Jordan, a Beaufort historian and Savannah tour guide, has researched the Pulaski tragedy, including its ties to Charleston.

The loss was felt most deeply in Savannah, where the Pulaski's fatal voyage originated and where most of the deceased had resided. Jordan noted that city cancelled its Fourth of July ceremonies for the first time in memory.

"They had a moment of silence throughout the town and asked people to wear black crepe armbands," he said.

The ship also carried 21 passengers from Charleston, only three of whom survived, including Robert D. Walker, Thomas Downie and G.Y. Davis, Jordan said. Four passengers were from Edisto Island, and they survived.

The Charlestonians lost included Thomas Pinckney Rutledge, Hugh S. Ball and his wife and child of Comingtee Plantation and Edward J. Pringle.

Also killed were New York congressman William B. Rochester and several members of the wealthy and prominent Lamar family of Georgia.

Of the ship's approximately 195 passengers and crew, only 59 survived, Jordan said.

"A lot of people think of it as a Georgia story but it's as much a South Carolina story as a Georgia story," he said.

Jordan wrote "The Slave-Trader’s Letter-Book: Charles Lamar, the Wanderer, and Other Tales of the African Slave Trade." Lamar had been a passenger on the Pulaski and was among the approximately 59 who survived.

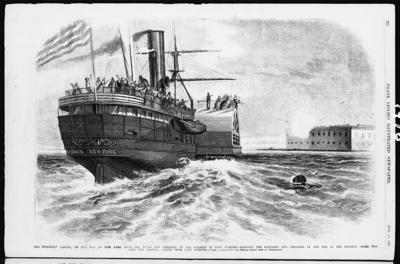

The ship advertised its trip as spending only one night at sea. It docked overnight in Charleston Harbor, where passengers slept in their berths. Then it left for Baltimore.

There were three main groups of survivors, Jordan said. One group managed to get onto two of the four lifeboats, and 18 of those 24 people survived, Jordan said. A chunk of the ship also remained afloat, effectively serving as a raft. Twenty-three survived on that. Another raft saved 13 others and six survived by holding onto a chair or another bit of floating debris, he added.

Some died immediately from the boiler explosion, Jordan said, "and most of the people were thrown into the water. Most of them drowned."

When news of the Pulaski first appeared in the Charleston Courier newspaper three days later, the article began, "Our community is again in mourning and tears. Another terrible visitation has wrung with anguish the bosoms of many and saddened the countenances and sorrowed the hearts of all our citizens."

The Pulaski's sinking came less than a year after the SS Home left New York bound for Charleston. It hit a sandbar off New Jersey, gradually took on water and was beached near Cape Hatteras, North Carolina, to ride out a storm. Before rescuers could arrive, the storm demolished the ship, killing 90 of its approximately 130 passengers and crew.

Last winter, the Florida-based Blue Water Ventures International and Endurance Exploration Group began working the Pulaski site. In May, they announced they had recovered two artifacts engraved with the name “Pulaski,” confirming the identity of the wreck.

Last month, it announced that it had found a “grapefruit-sized” encrustation that turned out to be a solid gold pocket watch, according to The Charlotte Observer. The watch's hands were frozen at 11:05, just minutes after witnesses reported the boiler blew. Other finds include coins, silverware, keys, and a mysterious gold box.

Keith Webb of Blue Water Ventures told The Charlotte Observer that he expects to find thousands of coins that could be worth millions. So far, they have recovered at least 51.

Jordan said Pulaski's newly found artifacts likely won't shed much light into the disaster, which already was documented by survivors. "Is there going to be anything earth-shattering that we learn about the times? I really don't think so," Jordan said.

But the newly recovered artifacts will help shed new light and provide new details about a story that many had forgotten.

"The more I dig into it, the more I realize all the stories that have been lost to history," he said, "and this is certainly one of them."