|

|

| Historical Hodgepodge:Dispatches from the Saco Museum |

|

|

|

New Acquisition for the Saco Museum

|

|

|

The Saco Museum ended the year 2025 with an exciting new acquisition for the museum collection in the form of a pier table, made in Saco at the Cumston and Buckminster shop, likely between 1809 and 1816.

Pier tables were designed to be placed against a wall, usually between two windows. The form is sometimes referred to as a console table. The pier table takes its name from the wall between windows, commonly referred to as the “pier wall” in England. Generally, a tall looking glass or mirror was hung over a pier table primarily to

|

|

|

Pier Table, 1809-1816 Joshua Moody Cumston and David Buckminster,

mahogany, maple, mahogany, birch, and stained wood veneers, pine |

|

|

reflect light from candles and other sources into an otherwise dark room. As the form developed, the tables were often constructed with mirrored glass between the two rear legs, a style that Duncan Phyfe, among others, popularized in the 19th century.

|

|

|

Pier tables with looking glasses above, Gyldenholm Manor, Denmark. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

|

|

|

|

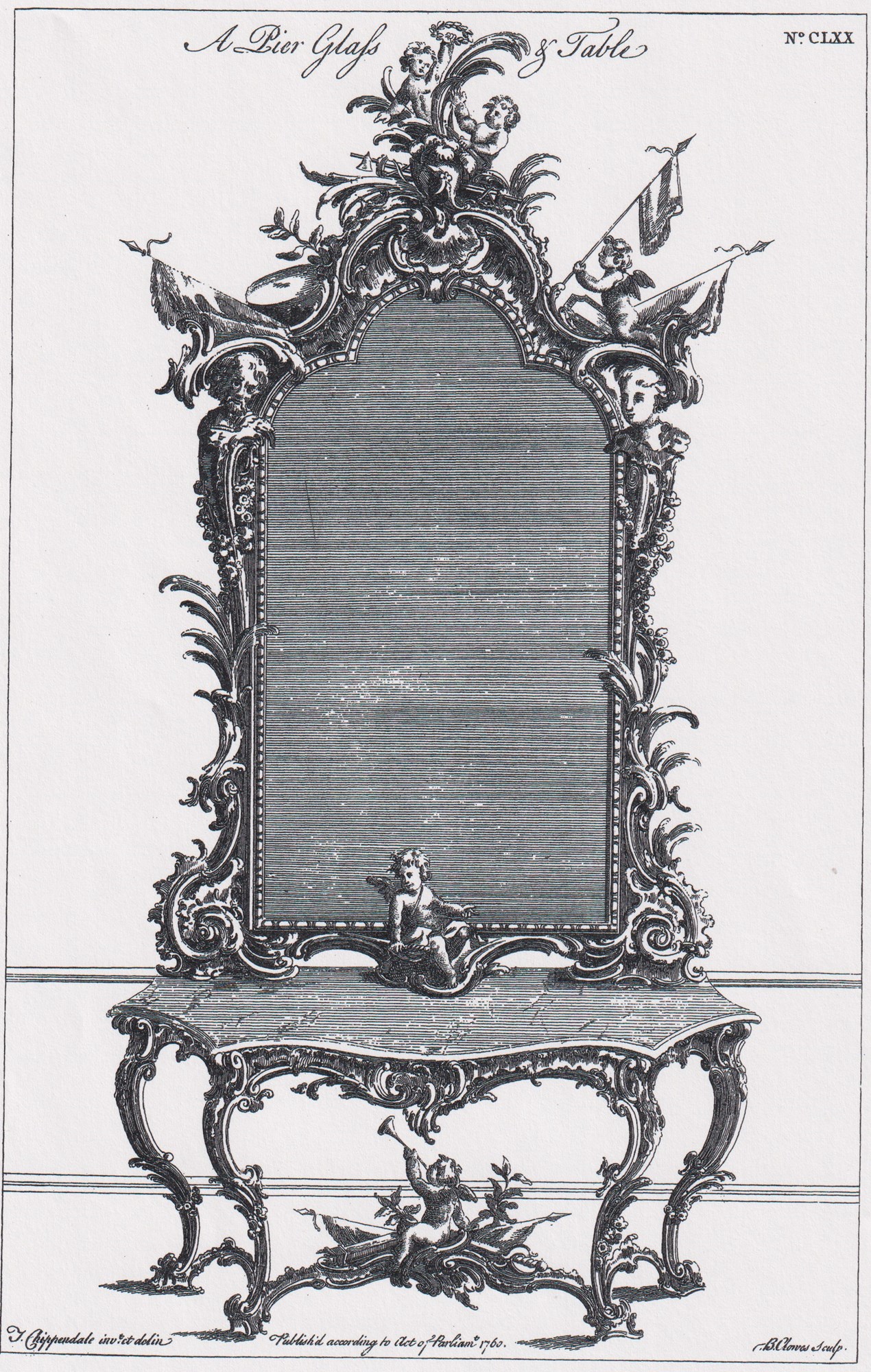

Pier table with looking glass from Thomas Chippendale, The Gentleman & Cabinet-Maker’s Director, 3rd. Ed., 1762 |

|

Originating in continental Europe in the 1500s and 1600s and reaching England by the last quarter of the 1600s, American colonists became aware of the pier table in the mid-1700s. In 1762, Thomas Chippendale published in The Gentleman & Cabinetmaker’s Director, an over-the-top design for a pier glass and table. While it is not likely that any Americans in the years before the Revolution commissioned such an elaborate ensemble from a local cabinetmaker, Benjamin Randolph of Philadelphia made a table for John Cadwalader in 1769 in the “new or French taste,” which was a streamlined version of Chippendale’s lavish design. Chippendale allowed for alterations to his design as he noted in the commentary on the illustration “A skillful Carver may, in the Execution of this…give full Scope to his Capacity.”

|

|

|

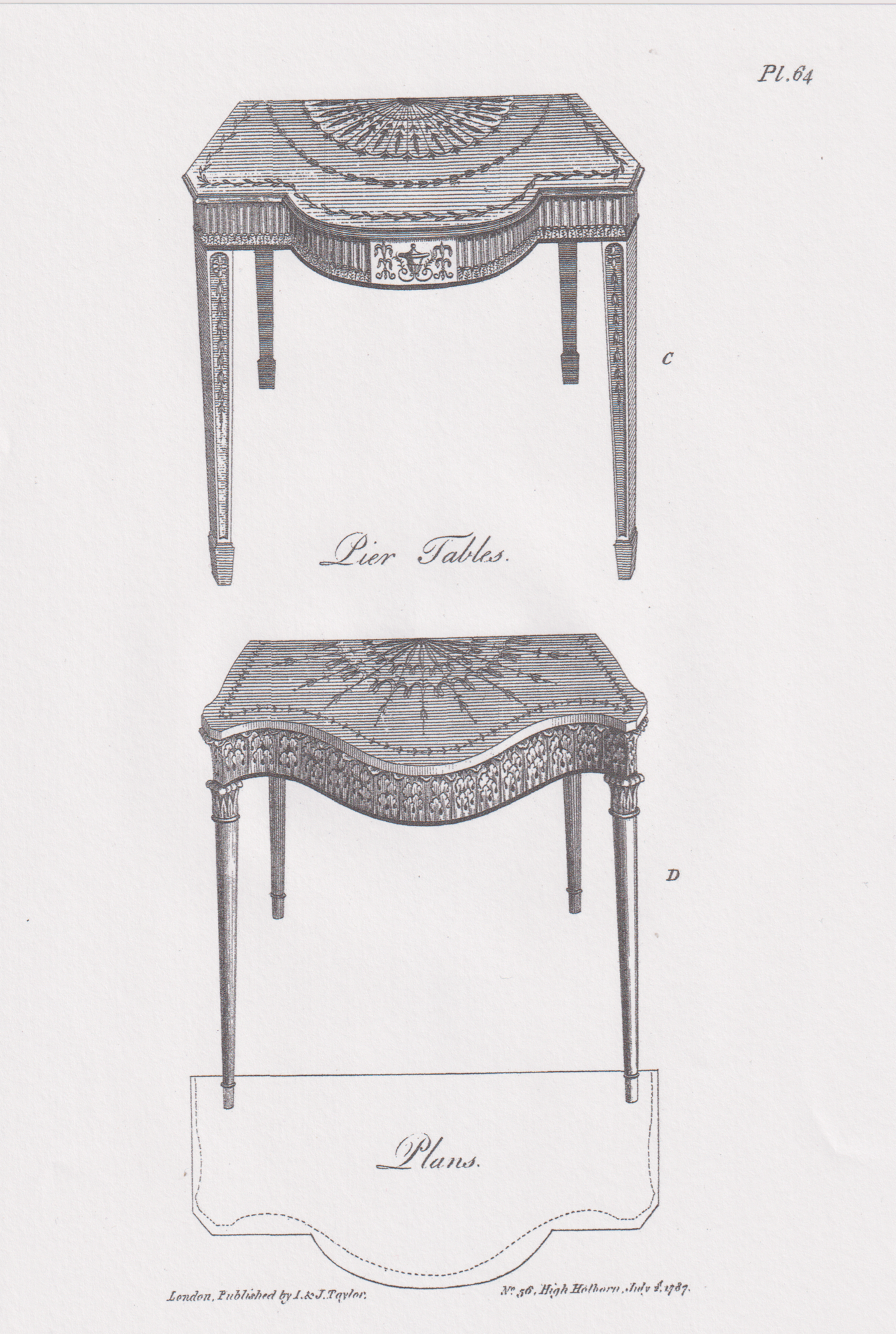

By the end of the 18th century and into the 19th, the Neoclassical style superseded the ornate decorative elements of the middle of the 18th century. George Hepplewhite and Thomas Sheraton published guides for cabinetmakers and upholsters in which inlaid decoration with contrasting woods rather than robust carving provided visual interest. Sheraton commented, “pier tables are merely for ornament under a glass [mirror], they are generally made very light, and the style of finishing them is rich and elegant” The essence of the pier table remained the same: the flat back edge was placed against the wall between the windows and the gracefully shaped skirt with a conforming top was elevated on four legs that were either tapered or turned as in the Saco Museum

|

|

|

Designs for pier tables, George Hepplewhite, The Cabinet-Maker and Upholsterer’s Guide, 3rd. ed., 1794 |

|

|

example. Our table is very similar to card tables produced by the same Saco shop but without the moveable leg that supported the hinged leaf of the top to allow space for four players. Card tables were designed to be placed against walls when not in use and moved out into the room as needed for games; pier tables were designed to be stationary and as so, the backs were not decorated to be seen.

Joshua Moody Cumston (1784-1835) and David Buckminster (1799-1849) worked together in a cabinetmaking and undertaking business in Saco from 1809-1816. They are credited with making some of the flamboyantly veneered furniture attributed to Portsmouth, New Hampshire, prior to Thomas Hardiman’s pioneering study and his article published in The Magazine Antiques, May 2001. In the article, Tom, a former curator at the Saco Museum, makes the point that “Cumston and Buckminster’s high-style furniture was not intended for provincial cottages but for highly sophisticated Federal interiors.”

|

|

|

|

Detail of inlay, Cumston and Buckminster pier table, Saco Museum, 2025.37.1

|

|

So far, this pier table appears to be unique in the output of Joshua Cumston, David Buckminster, and Abraham Forsskol, a native of Sweden who joined the company in 1815. Helping to place the table as a product of the shop is the double stripe-on-bar and diagonal inlay that also appears on a chest of four drawers with inlaid ovals from the same shop. The location of the chest of drawers is currently unknown.

|

|

|

The pier table was donated to the Saco Museum as a gift from the Birch Lodge Fund of Fox Point, Wisconsin. We are grateful to Tom Hardiman and Gerald W. R. Ward, a noted furniture scholar, for their efforts in steering the pier table to the museum. On your next visit to the Saco Museum, look for it in one of the alcoves to either side of the front door.

|

|

|

|

The Hooked Mats of Grenfell Industries

|

|

|

|

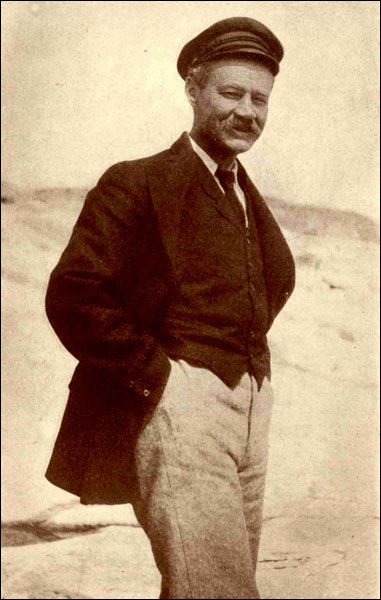

Sir Wilfred Grenfell,

circa 1910 |

|

|

In 1892, Sir Wilfred Grenfell (1865-1940) arrived in Labrador. He was sent by the United Kingdom’s Royal National Mission to Deep Sea Fishermen to investigate living conditions among the local fishermen. Grenfell was shocked by the region’s poverty and lack of medical facilities and embarked on an effort to raise funds to establish regular health-care services in Labrador. He formed the Grenfell Mission (later the International Grenfell Association) and a series of hospitals were established and medical ships acquired to cruise the coastlines of Labrador and Newfoundland.

|

|

|

The mission also sought to make social changes in the areas of education, agriculture, and industrial development. In addition to providing medical care, mission workers built schools, and helped establish lumber mills, community farms, cooperative stores, and a commercial handicraft industry. Grenfell felt strongly that outright gifts of money, food, or clothing would not offer the necessary long-term help to the people of the regio. He believed that the best way to help to improve their standard of living was for them to develop their own cottage industry. The Grenfell “Industrial” department was founded and became most famous for its textile

|

|

|

Jessie Luther, age 40,

circa 1900 |

|

|

arts, particularly hooked mats and rugs. One of the key people in developing the products of the Industrial department was Jessie Luther (1860-1952), an American who was an early proponent of occupational therapy. Grenfell met Luther in 1905 and invited her to join the mission in Labrador. She arrived the following year and set to determining what type of handcrafts might best be developed into a home industry.

The winter months of February and March had long been known as the “matting season” along the coasts of Labrador and Newfoundland. The women of these regions, descendants of the early English and Scottish settlers, all hooked, most of them from an early age. Mat hooking was easily accomplished at home with the use of a simple frame and hand-made hook, but at first it was overlooked as a potential cottage industry. Jessie didn’t mention mat hooking until January 29, 1908, when she noted in her journal,” This afternoon was the beginning of the matting club. Several women came by evidently with the idea of looking around before committing themselves.” The low attendance at that first meeting may have been because so many had already mastered the craft and developed their own designs - often blocks or triangles arranged like patchwork or floral designs.

|

|

|

|

Jessie Luther on snowshoes, 1909 |

|

Originally the mat hookers used wool from fabric scraps and worn out clothing that they hooked onto old burlap sacking they called brin. The local women tended to like bright colors, which the Grenfell Industrial supervisors did not approve of. Ultimately, the mat hookers were required to work to standards set by the Grenfell people. The supervisors decided on what the patterns should be, chose the materials, and set the colors–harmonious pastels rather than bright colors–and made sure the final product was of an acceptable quality. In order to ensure the appearance of the final product, workers were given kits that consisted of a design drawn on burlap, and 12-18 yards of hooking material torn into ¼” x 10” long strips. A

|

|

|

colored drawing or scraps of hooking fabric pinned to the appropriate area were also included to be sure that the correct color scheme was followed. Kits were distributed to the mat hookers by Grenfell workers who traveled along the coast by boat or dog team. Jessie Luther was one of those who journeyed thousands of miles along the coastlines to distribute raw materials and pick up finished mats. By 1916, sixteen different patterned mats were in production, mostly distinctive northern scenes of dog teams, bears, hunters, and birds. A decade later, the production of hooked mats had reached assembly-line efficiency.

In the early years wool was used as a hooking material, but by the mid-1920s silk was more commonly used. In 1928, the supervisor of the Industrial sent out a plea through the mission’s newsletter for silk stockings: “Save Your Old Silk Stockings! When your stockings run, let them run to Labrador!” The silk was then dyed in a range of soft hues, which proved to be very popular and helped propel the mat industry into its years of peak production. Most of the Grenfell mats found today were produced between 1926 and the early 1930s. By the winter of 1929, 3,000 mats had been hooked and the revenue for sales had risen from $27,000 in 1926 to $63,000 in 1929.

During the early 1930s, mission volunteers toured the resort areas of New England and New York selling the mats. Eventually, retail shops were opened in New York City and Philadelphia where urban shoppers were happy to purchase the mats with their distinctive images. Unfortunately, the Depression years took a toll on the mat-making industry. After nylon was invented in 1938, it became difficult to find sources of the formerly common silk and rayon stockings. With the death of Grenfell in 1940, the driving spirit behind the “Industrial” faded away. |

|

|

Today, Grenfell hooked mats are regarded as a form of folk art and are highly sought after. They are distinctive not only for their subject matter but because of the use of straight horizontal line hooking and the denseness of the hooked material. The mat in the Saco Museum collection is 10’ high and 7 ½” wide and depicts a woman on snowshoes walking through the woods with a gun held over her shoulder. According to the accession record, it came to us from the “Dennett house,” presumably the home of Dorothy Dennett (1901-1981).

|

|

|

Female hunter, silk or rayon stocking material, circa 1925-1935. |

|

|

|

Remembering the Revolution,

June 27-September 5, 2026 |

|

|

This year marks the 250th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence. The American Revolution gave birth to a new nation and set of ideals that have been memorialized and reimagined ever since. Remembering the Revolution will feature stories of some of those involved in the conflict, such as Benjamin Simpson, a local mason who participated in the Boston Tea Party and later served in the Continental Army and Captain Jabez Lane of Buxton who fought in campaigns from Boston to New York. The exhibition will also look at how later generations shaped our understanding of the Revolution. After the war, people began saving items connected to the event or associated with those who played a role in the new nation, like George Washington and over the course of the 19th century, mass-production made products with Revolutionary War imagery affordable. The Centennial celebrations in 1876 served to reinforce national unity after the Civil War and emphasized the nation’s history as a triumph of liberty and democratic progress. The Bicentennial in 1976 focused on many of the same themes: national renewal, patriotism, and a nostalgic reflection on the American past, coming as it did after the Vietnam War years and Watergate. Yet neither of these celebrations told the full story of the struggle for liberty or acknowledged the ways in which the United States had failed to live up to some of the ideals put forward in the Declaration.

To do justice to the story of the Bicentennial, we need your help! We would like to include Bicentennial memorabilia in the exhibition and are looking for items that we could borrow. If you have something you think we would be interested in that we could have from May through early September, please contact Tara Raiselis at traiselis@dyerlibrarysacomuseum.org.

|

|

|

|

|

|