|

|

Maine girls knitting in 1942 | | Historical Hodgepodge:

Dispatches from the Saco Museum | |

New Hours! | Starting Thursday, January 23, the museum will be open until 8:00 pm on Thursdays, rather than Fridays. Admission will be free after 4:00, as it has been on Fridays in the past. |

|

|

|

|

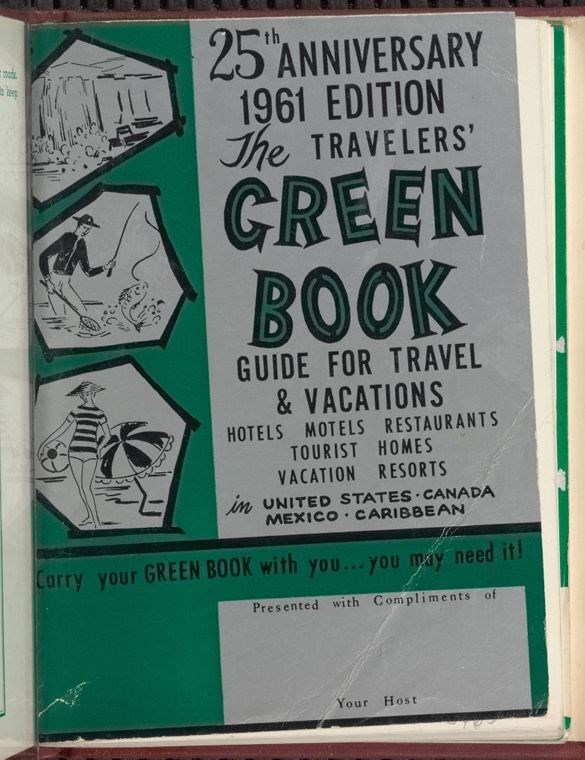

1961 Green Book |

|

We recently received a request for information about Coley’s Acres, an African American resort located on Portland Road in Saco in the mid-20th century. The resort was listed in the 1960 and 1961 editions of The Negro Motorist Green-book, an annual guidebook for African-American travelers published from 1936-1967. The Green Book became an indispensable guide to travel during the Jim Crow era, when

|

|

|

discrimination against African-Americans and other non-whites was widespread and often quite legal. The Guide was designed to identify services and places friendly to African-Americans so that they could find safe lodgings, businesses, and gas stations that would serve them.

| |

From what we have been able to discover so far, Coley’s Acres was composed of a ten-acre lot with a seven-room house, two cabins, and an outdoor recreation building. It was located across from the Traveler’s Motel and next door to King’s Cabins. We are trying to determine exactly where it was located (a street address would be great!) and what is on the site today. The researcher who contacted us is trying to map all the Green Book locations in New England. |

|

|

|

|

Images: Postcards of Traveler’s Court Motel and King’s Cabins.

| We are hoping that someone in the community can help us find out more. If anyone has any additional information, please email traiselis@dyerlibrarysacomuseum.org. We really appreciate your help! |

|

|

|

|

One of the more unusual objects in the Saco Museum collection is a piece of wood from George Washington’s coffin. As odd as this relic is, fragments of Washington’s coffin are found all over the United States in local museums and personal collections, and often appear in auctions. This piece of mahogany is extremely light and measures about 5 1/2 inches long and an inch wide. An inscription in pencil on one side says “1838”; the writing on the other side is illegible.

|

|

|

|

Coffin fragment |

After Washington’s death in 1799, his body was placed in a lead-lined mahogany coffin which was surrounded by an outer wooden case covered in black fabric. He was laid to rest in the old family tomb until a new family crypt could be constructed, as Washington had instructed in his will. However, progress on the Washington mausoleum was slow and the new tomb wasn’t completed until 1831. Final construction was spurred on by the large influx of “pilgrims” and random vandalisms that occurred at the Mount Vernon family memorial over the years. |

|

|

In 1831, George and Martha Washington’s remains were relocated from the old Washington family crypt to a new brick tomb at Mount Vernon. The original tomb was damp and by the time Washington’s

|

|

|

original Washington vault |

|

|

body was moved, the outer coffin had deteriorated significantly. John Augustine Washington III (1821-1861), who was the great-grandnephew of George Washington and last private owner of Mount Vernon, broke apart Washington’s deteriorating coffin and distributed the wood pieces as souvenirs to friends and associates of the family. Finally, in 1837, a marble sarcophagus was erected for Washington and his lead-lined coffin was placed within this new vault, where it remains today.

|

|

|

John Augustine was greatly disturbed by the constant unannounced visitors to the Mount Vernon estate, but the property was lacking in funds and in a state of severe disrepair and he

|

|

|

new Mount Vernon tomb |

|

|

ultimately was forced to make a difficult decision. He reluctantly embraced the idea of transforming Mount Vernon into a tourist destination. Tour boats were eventually allowed to dock at the property and John Augustine sold various souvenirs, including possibly the pieces of the coffin. He eventually sold Mount Vernon to the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association in 1858 for $200,000. John Augustine was later killed in battle in 1861 while serving under General Robert E. Lee.

| | New Exhibit opens February 22 |

|

|

|

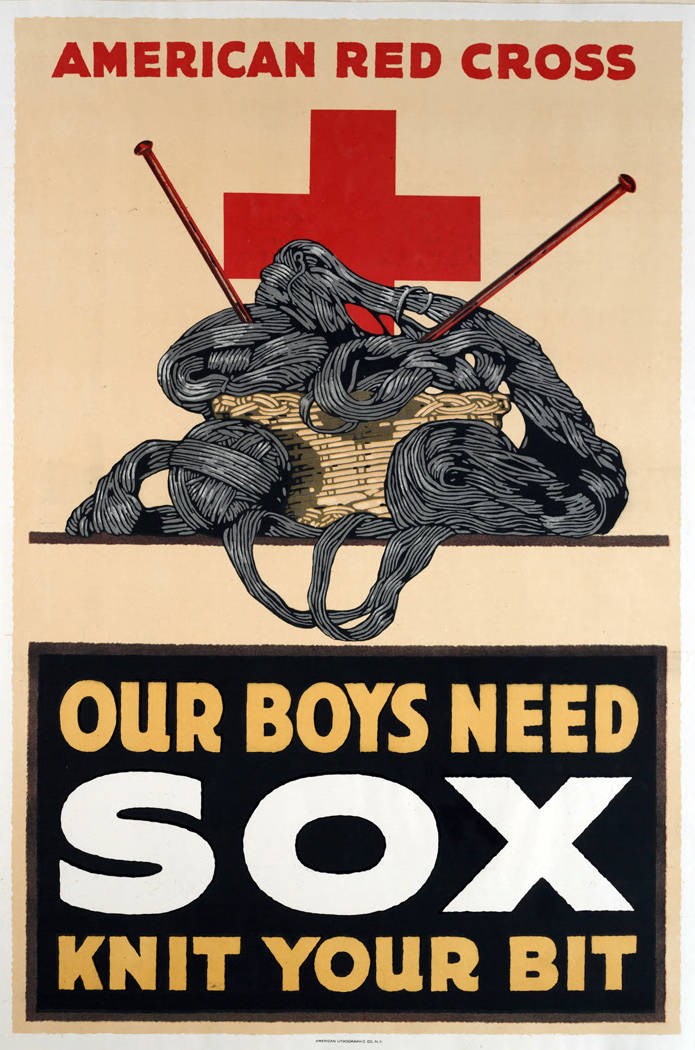

Red Cross poster circa 1918 |

|

Are you a knitter? Even if you’re not, you will enjoy our upcoming exhibition “Tending to Our Knitting: Traditions and Trends." Based on the collection of Jacqueline Fee, author of The Sweater Workshop, the exhibition will feature an array of historical knitted home goods and garments. From 19th-century baby bonnets to 20th-century fashionable sweaters, from knitting sheaths to red, white, and blue patriotic World War I knitting needles, we will explore the role

|

|

|

knitters played in producing domestic items for the home as well as the important public roles they played in providing soldier’s necessities during wartime.

| |

Jacqueline Fee published the first edition of The Sweater Workshop in 1983; a second edition was published in 2002. It was written for creative knitters who didn’t want to have to follow a pattern blindly and |

|

|

instead wanted to be able to master the techniques that would allow them to design their own seamless sweaters. Along with Elizabeth Zimmerman’s publications, such as Knitting Without Tears (1971), Fee’s book was an important part of the movement away from producing garments as a series of flat pieces to be sewn together and towards custom designed sweaters knit in the round.

|

|

|

cover of the Sweater Workshop |

|

|

|

|