|

|

| Historical Hodgepodge:Dispatches from the Saco Museum |

|

|

|

|

Sometimes one acquisition for the Saco Museum collections leads to another and in the process, informs us about a part of the past of which we are only mildly aware and rarely include in our interpretive exhibitions. This happy coincidence took place earlier this year beginning with a typical weekend perusal of a website belonging to an antiques dealer in England who specializes primarily in English pottery.

|

|

|

On the website, an image for a pearlware pitcher commemorating the Maine Law was posted. Curiosity was piqued and research indicated that the Maine Law was the culmination of several decades of increasing efforts to suppress the intemperate use of alcoholic beverages in Maine. Early adopters formed Maine’s first temperance association in 1813 while the District was still a part of Massachusetts. Members of the Massachusetts Society for the Suppression of Intemperance had chapters in Portland and Saco which sought to “suppress the too free use of ardent spirits, and its kindred vices, profaneness, and gaming; and to encourage and to promote temperance and general morality.”

|

|

|

Pitcher, “A PROHIBITORY LIQUOR LAW FOR THIS COUNTRY”, ca. 1855 Beech, Hancock & Co., Burslem, England

pearlware with green slip, ink, and gilding Museum purchase |

|

|

Moderation in the use of ardent spirits was advocated, not total abstinence. The latter would become a powerful force under the leadership of a young man, Neal Dow, who formed the Portland Young Men’s Temperance Society in 1833, promoting total abstinence from hard liquor.

Fast forward to 1850 when Dow, after unceasing efforts, introduced a bill in the legislature banning the manufacture and sale of alcohol except for medicinal and mechanical use. The bill failed but passed in June 1851 and became known as the Maine Liquor Law or “Maine Law”. As well as prohibiting the manufacture and sale of alcohol except for medicinal and mechanical use, a local agent was to be appointed in each town to oversee the sale and storage of liquors for these purposes, and violation of the law was punishable by a fine and jail time for repeat offences.

|

|

|

|

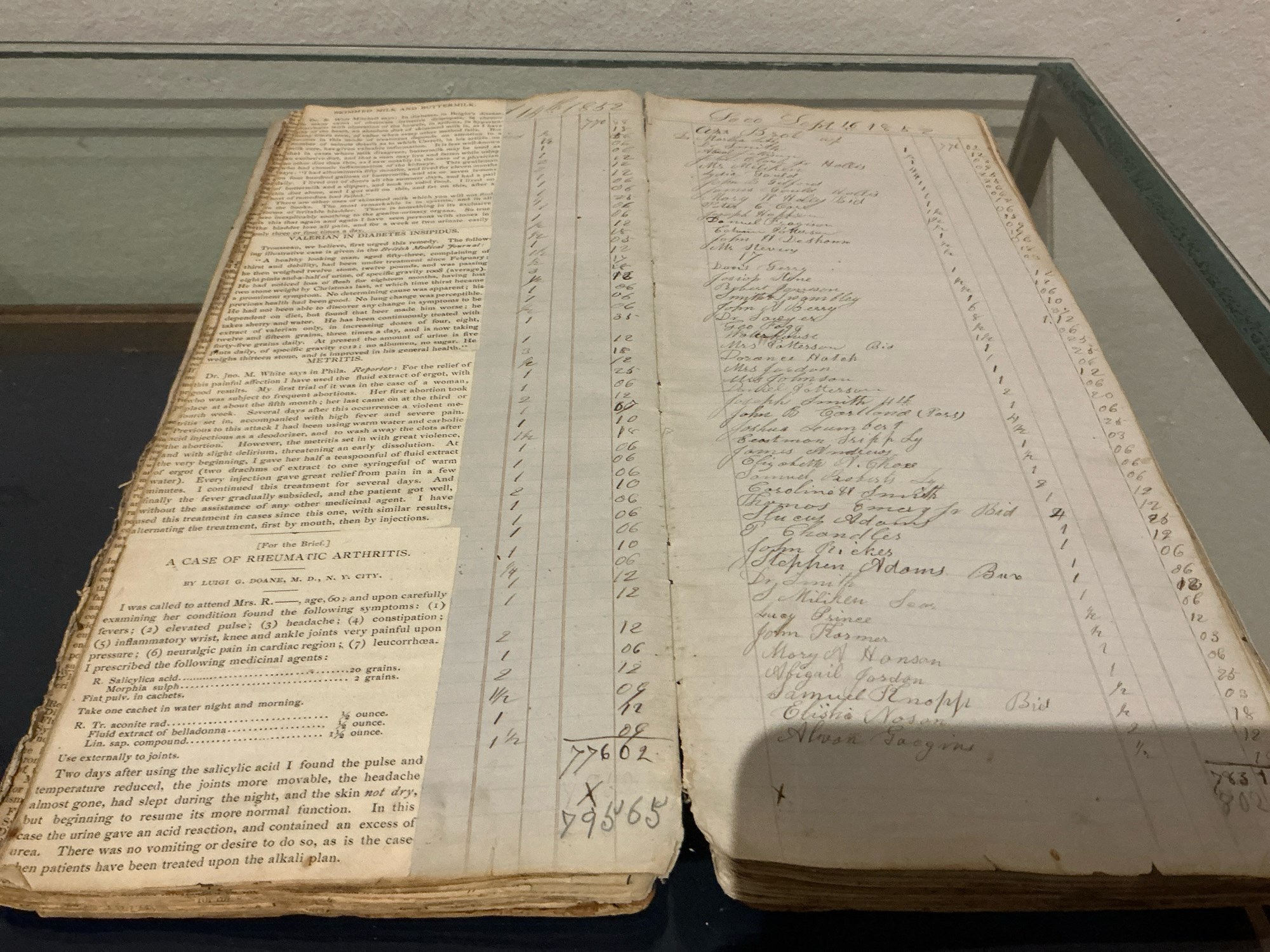

The Town Liquor Book, 1852-1853,

with later use as a scrapbook

John A. Berry, Agent for Saco, Saco, Maine leather, paper, and ink gift of Betty Shreck Griffis

|

|

This information became even more interesting after an email arrived from Arizona asking if a “ledger” which descended in their family would be appropriate for the museum collection. After a positive response, the ledger soon arrived. While part of the ledger was eventually used as a scrapbook, many of the original pages were still visible and documented the efforts of one John A. Berry. In The Town Liquor Book, 1852-1853, Berry, the agent for Saco, enumerated his dispersals of liquor in Saco during this

|

|

|

time, to whom, the town where they lived if other than Saco, and in what amount, as required by law.

Acquiring the pitcher then made even more sense because, combined with the ledger, it would help to tell the story of an important part of Maine history that lasted until the repeal of National Prohibition in 1934. The pitcher was still available in England and we were able to purchase it. Manufactured by Beech, Hancock & Co. Burslem, England, the pitcher was made specifically for the American market about 1855. After the “Maine Law” was enacted, neighboring states used the law as a model and passed similar reforms. The movement which began in Maine garnered regional, national, and international attention. British manufacturers took notice and made items promoting what was referred to as the “Maine Law,” even as it was enacted in other states.

|

|

|

|

|

During this past summer, the Saco Museum staff invited visitors to the museum to go “Behind Closed Doors: the Secrets of Museum Work” and get a glimpse of what is involved in caring for a diverse collection of artifacts. Museum staff used the opportunity to mount in the main gallery an exhibition

|

|

|

featuring new acquisitions as well as items collected during the early years of the museum, which was founded as the York Institute in 1866. Case studies presented around the perimeter of the room included an area devoted to condition and conservation, highlighting the value of original materials to an understanding of an artifact as well as a discussion of remedial treatments to stabilize and repair damage inflicted over time to two different paintings. The value to the collection of two “separate but equal” chests of drawers recently acquired was also discussed with interpretative panels explaining why each one has an important role in the collection. The histories and stories behind the objects selected for the exhibition were also highlighted. The stories of the Staples family as well as the ladies of the Methodist Church in Saco were represented through paintings and documents.

|

|

|

Tools and equipment for museum work were also on exhibition. Examples of photographic equipment and a slide projector represented the best the late 20th century had to offer in the pre-digital age while a typewriter was essential before the advent of desktop computers. In spite of the technological developments, current staff still depend on magnifying glasses, ultraviolet lamps, needle and thread, brushes and pens, tape measures, and gloves to do their everyday work.

|

|

|

A highlight for visitors was the opportunity to see staff at work in the gallery, reviewing, accessioning, cataloging, researching, cleaning, and storing (packing and boxing) various artifacts on large tables at one end of the gallery. We welcomed staff and volunteers from as far away as Texas, Arlington

|

|

|

National Cemetery, the Smithsonian and closer to home a number of local historical societies and small museums. It was an excellent opportunity to answer questions, share information, and meet people working in the museum field.

The summer exhibition was extremely productive! We catalogued 97 items and packed 50 new boxes. There is still much to do, however, and we plan on continuing to go through the roughly 100 boxes that are still left to examine. In order to accomplish this, we have moved our workspace to the second floor of the museum in the room across from the Mill Girls’ exhibit. |

|

|

|

Nineteenth-Century Men’s Wear

in the Saco Museum |

|

|

The clothing items that end up in museum collections are rarely representative of the range of garments worn in the past. Most people tend to save special occasion attire or other items that they have some sort of sentimental attachment to, such as wedding dresses or children’s clothing, while seldom making a point to save their more mundane everyday clothes. People also are much less likely to save men’s clothing of any sort, which is why we are fortunate to have a number of examples of everyday men’s clothing from the 19th and 20th centuries in our collection. Below are a few examples; you can see more at https://hub.catalogit.app/saco-museum/folder/clothing-and-accessories. While we don’t know who originally wore the leather breeches, the other items all were owned by local men.

|

|

|

Leather breeches, 1800-1830.

Since leather can stretch to conform to the body, leather breeches were durable and practical for activities that required a lot of movement. For that reason, many tradesmen wore leather breeches when working. By the early 19th century, fashionable men began to adopt the styles of some working people as their own. Leather breeches provide an excellent example of this fashion trend, since in the early 1800s, wealthy men began to wear them as stylish items of clothing, while working people continued to wear them because they were functional. These breeches were probably worn for riding. |

|

|

Cotton checked vest, 1850-1860. Gift in memory of Doris Tapley Clark by her children.

Many people would not consider this vest a “fashionable” garment. Although relatively simple in construction, without a lining, and of an inexpensive cotton material, it shows that the interest in current styles affected the design of everyday clothes. Checked vests were particularly popular in men's clothing in the late 1850s. They were frequently worn with checked trousers, not always matching in scale or color, which probably made for some very eye-catching combinations.

|

|

|

Wool frock coat, 1855-1865.

Gift of Roy, Maryllyn, and Donna Fairfield.

By the mid-19th century, the frock coat was considered an essential part of a man's wardrobe. Although they were made of a variety of fashionable fabrics, black wool was probably the most common material. Frock coats worn with straight trousers, a short vest, and a shirt with a high collar formed the basic man's “business suit” of the 19th century.

|

|

|

Wool broad-fall pants, 1880-1900. Gift of Roy, Maryllyn, and Donna Fairfield.

These pants are a great example of everyday work clothes, something that rarely survives to end up in a museum collection. They are of a heavy wool twill and are entirely hand-sewn. They also are heavily patched with a similar wool twill, with four patches on the front of the legs and two oval patches on the seat of the pants. They were clearly worn for many years before being put away.

|

|

|

|

|

|